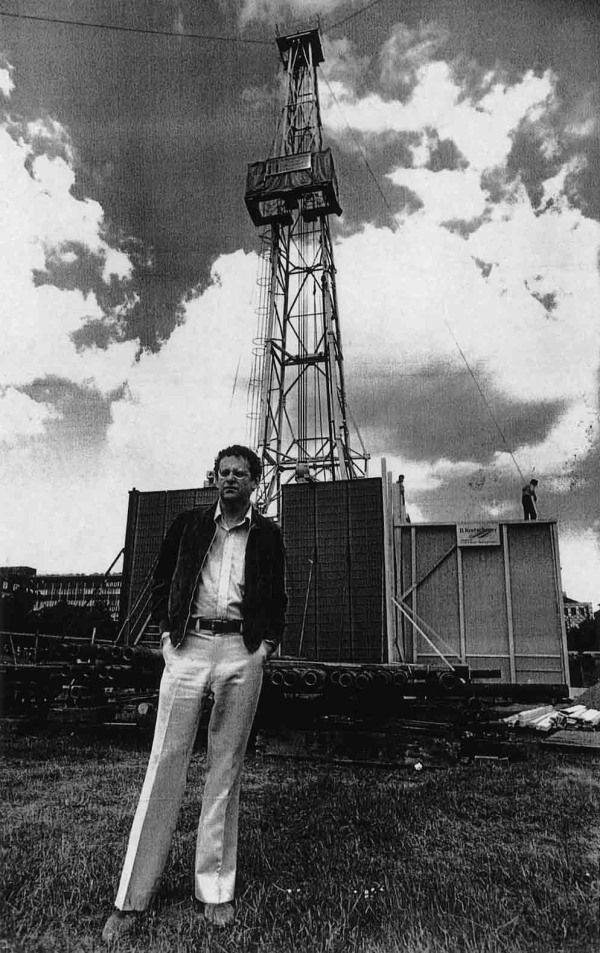

Performance, Friedrichsplatz Kassel, 14 May 1997

Performance, Friedrichsplatz Kassel, 14 May 1997

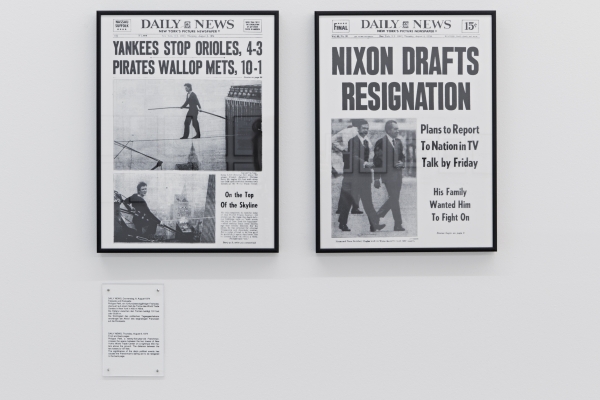

Installation view, The Balancing-Act, Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Kunstmuseum Basel

Installation view, The Balancing-Act, Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Kunstmuseum Basel

Installation view, The Balancing-Act, Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Kunstmuseum Basel

Installation view, The Balancing-Act, Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Kunstmuseum Basel

Walter de Maria, "Vertical Earth Kilometer," 1977

Joseph Beuys, "7000 Oaks," 1982-1987

"A Balancing Act," 14 May 1997 (video excerpt)

A Balancing Act

In: documenta x

21 June – 28 September 1997

documenta X, Fridericianum, Kassel, Germany

Performance:

– “A Balancing Act,” Friedrichsplatz Kassel, Wednesday, 14 May 1997, 10:00 am, ca. 60 min.

Elements of the Performance:

– Tightrope

– Balancing rod, oak and brass

Contributor:

Heinz Jürgen Weidner

Exhibition Space:

– “A Balancing Act,” 1997, oak and brass on a base, monitor with the video “A Balancing Act,” 20 min., camera: Jan Lackner, photographs and documents, framed and labeled with signs, wall text, collection of the Kunstmuseum Basel

Catherine David, artistic director of documenta X, conceived the 1997 exhibition in Kassel as a “retroperspective,” a situating of the present with a view to the past. Christian Philipp Müller focused his backward gaze on the location of documenta and its changes, uncovering the traces left by other artists in the vicinity of the Museum Fridericianum. On the third floor of the building, Müller designed an exhibition space oriented to the sole window on that floor opening onto Friedrichsplatz, uncovered from behind a wall. The exhibition area itself focused on two works installed in public space: Joseph Beuys’s “7000 Oaks” from documenta VII and Walter de Maria’s “Vertical Earth Kilometer” from documenta VI.

De Maria had wanted to realize his piece as a conceptual work in public space. A five-centimeter-thick brass rod was inserted one kilometer deep into the earth; viewers in Kassel were supposed to see only the tip, sunk into Friedrichsplatz. Contrary to de Maria’s intention, however, the elaborate drilling process became as much of a spectacle as the attempts to conceal the installation work. On 6 May 1977, the latter was concluded and the brass rod was inserted into the earth on the site where the paths across Friedrichsplatz intersect in front of the Fridericianum.

Joseph Beuys’s action “7000 Oaks,” on the other hand, was a radically participatory work. 6999 basalt steles were piled up in front of the Fridericianum in preparation for planting next to an equal number of oaks throughout the city of Kassel. In 1982, Beuys planted the first oak together with the first stele in front of the Fridericianum; in 1987, his family set the 7000th stele and oak next to it. By that time, 6998 pairs of steles and oaks had been distributed throughout the urban area of Kassel. Müller’s investigation addressed both the fundamental difference between these two works as well as the ongoing effect of the urban structure on both installations. The construction of an underground parking garage beneath Friedrichsplatz in 1996 has changed its structure: De Maria’s “Earth Kilometer” is no longer located at the center of intersecting paths, and Beuys’s first and last oaks have likewise shifted away from the center of the visual axis.

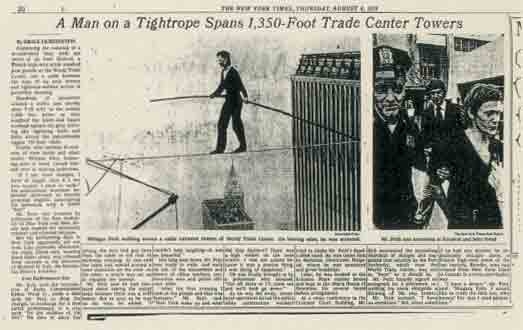

In a performance for the media, Christian Philipp Müller paced off the distance between Beuys’s and de Maria’s works. Dressed like the tightrope walker Philippe Petit, he balanced on a rope stretched out on the ground between the two works, carrying a six-meter-long balancing pole made of half oak and half brass. Petit had practiced secretly for a number of years when, in an unannounced and highly sensational performance on 7 August 1974, he balanced on a steel cable stretched between the over 400-meter-high towers of the World Trade Center in New York. He was arrested, and as punishment had to repeat his tightrope act for children in Central Park.

In the exhibition space, Müller’s performance was presented as a past event on a video monitor across from the window. The balancing rod, placed on a pedestal, divided the space into two: at one end was the window looking out onto the square, at the other was the video of the balancing act. On the window wall, the history of Friedrichsplatz was combined with that of documenta. To the left and right of the window, framed and accompanied by commentary on Plexiglas panels, illustrations and texts documented the production and financing of the two works outside the window (and therewith the difficulties of art in public spaces at documenta) along with a quotation by Gordon Matta-Clark.

Essay by Philipp Kaiser available here.

Exhibition Brochure: "A Balancing Act"

“I like natural disasters, and I think that they mav be the highest form of art possible to experience. If all of the people who go to museums could just feel an earthquake."

— Walter de Maria

"We are planting trees everywhere that the people want to have

trees...and Kassel is only the beginning. Afterwards, it will continue all the way to Siberia. "

— Joseph Beuys

Dia Means "The Godlike One"

The Dia Art Foundation was founded in 1974 by Heiner Friedrich in New York City. Dia covered the entire expense for Walter de Maria’s “The Vertical Earth Kilometer” — $419,000 in 1977. “7000 Oaks” by Joseph Beuys received an initial startup sum from the Foundation in the amount of 280,000 DM for the installation of the basalt stones on the Friedrichsplatz. De Maria’s “Broken Kilometer” (a work based on the Kassel piece) has been on view in New York since 1979; a continuation of “7000 Oaks” has begun around Dia’s New York address since 1989.

THE RETROPERSPECTIVE

One of the more melancholic, at times devastating, laws of history lies in the fact that it is only with the decay of a given object — with the ruination of an institution, the break-up of a cultural formation, the obsolescence of a concept — that its history becomes visible for the first time, that it becomes available for historical contemplation. What then are we to make of a documenta exhibition defined by its curator as a "retroperspective," as an exhibition that will look back upon its predecessors to more clearly define the cultural situation of the present?

ETERNITY

Following a suggestion by Catherine David, Müller's project for documenta X began with a simple question: what physical traces have been left in the city of Kassel after nine documentas? Noticing during the course of 1996 that the Friedrichsplatz had been disfigured for the construction of an underground car park, Müller became interested in the two site-specific sculptures still to be seen there: Walter de Maria's “The Vertical Earth Kilometer” and the first and last trees from Joseph Beuys' “7000 Oaks” project. Before the opening of documenta 6, on May 6, 1977, construction began on De Maria's work, a sculpture that involved the drilling of a hole one kilometer into the earth; a solid brass circular rod, two inches in diameter and one kilometer long, was dropped into the hole. The sculpture's placement originally marked the center crossing of the pathways that bisect the Friedrichsplatz. Joseph Beuys' documenta 7 proposal was to plant 7,000 oak trees throughout the city of Kassel; Beuys planted the first of the oak trees with a basalt stone marker in the Friedrichsplatz on March 16, 1982. After Beuys' death in 1986, the last of the 7,000 trees was finally planted next to the first by Beuys' widow and his son to mark the opening of the next documenta in 1987.

In their different ways, both projects had evidently left the physical frame of the museum, opting for placement in the urban space of Kassel. But had they truly escaped their institutional frame? On the Friedrichsplatz, De Maria's earthwork and the first and last of Beuys' trees seem to act as little more than logos for the museum building standing directly behind them.

While participating in the permanence implicit in many sitespecific projects, these works push that definition onto a qualitatively different level: they aim to be eternal both in their material embodiment and artistic implications. The sovereign desire upon the part of both Beuys and De Maria to mark the face of the city permanently was a desire eventually deflated by the city of Kassel itself. With its construction of a car park completed during 1996, the city literally pulled the rug out from beneath both works by redesigning the very face of the Friedrichsplatz. De Maria's “Vertical Earth Kilometer” no longer marks the center of the place today; it has been shunted off to one side, almost forgotten in the grand sweep and new symmetries of the plaza. Beuys' trees and basalt stones are also now placed in a completely illogical proportion to the path system.

A split between the site and the art — a split that echoes the long emerging one between documenta and Kassel — now registers physically on the skewed face of the Friedrichsplatz.

A DIALECTICAL IMAGE

With the “Vertical Earth Kilometer” and the key trees from “7000 Oaks” squarely facing each other upon the Friedrichsplatz, it is as if the internal history of the documenta exhibitions had concretized what Walter Benjamin has called a "dialectical image," an idea he clarified as "dialectics at a standstill."[1] For the projects of Beuys and De Maria seem to represent the two poles between which art in the twentieth century has always oscillated, the irreconcilable "torn halves" that the entire avant-garde project of the twentieth century has not yet been able to bridge: the aesthetic and the social spheres, art that defines itself as a pure aesthetic construct and avant-garde projects that aim at pure social effectivity.

A CIRCUS ACT

And what of the contemporary artist today, presented to an international audience at documenta X in 1997? One could see Christian Philipp Müller's "exhibition within an exhibition" as a retreat. Müller chooses to withdraw into the museum itself, occupying a space within it that frames a vista back onto the Friedrichsplatz. A space is thus provided for contemplation of the current state of the urban space, the skewed “Vertical Earth Kilometer,” and Beuys' oak trees — a space resolutely within the frame of the museum, one that attempts to provide a contemplative distance within which to regard the recent and seemingly irreconcilable difficulties that plague the attempt to create a truly public art. In this space, a brief history of the Friedrichsplatz is presented; documents relevant to the funding of the two sculptures are displayed. Finally, Müller places a six-meter long balancing rod upon a sculptural base, a bar constructed half in brass, half in oak (loosely pastiching De Maria's “The Beginning and End of Infinity,” 1987). The placement of this sculpture punctuates the vista's continuation into the room within the museum.

At the apex of this vista, Müller has embedded a video screen within the wall of the Fridericianum. Here, a video plays, showing a performance recorded before the opening of documenta X. Along the lines of his previous projections of himself as a Dutch king, a backpacking tourist, and (most recently) Jacques Tati, in this performance Müller identifies himself with a specific tightrope walker named Philippe Petit. In the video, it becomes immediately evident that Muller's sculpture is also an object of use; outside of the Fridericianum's frame it evidently has a specific function, a function belied by the rod's reification into an immobile, abstract object within the museum as well as its presentation to the viewer as if in a dream-like past tense, recorded on video. Balancing bar in hand, Müller precariously and repeatedly walks the distance between the “7000 Oaks” and “The Vertical Earth Kilometer.” With neither the financial support of a foundation nor the market value of Beuys or De Maria, Müller presents an allegorical image, resurrecting the form of one of the most debased vestiges of bourgeois entertainment, the residue of an outmoded, by now quaint spectacle in comparison to the spectacular panorama of the contemporary documenta: the circus performer, a figure of immense attraction for the early twentieth century avant-garde for its already apparent decrepitude. Slowly, methodically, Müller does nothing but use the performance to trace a very specific line between the two sculptures. While Beuys did not position his tree in a set relationship to the De Maria, Müller's emphatic connection of the two serves to underline the fact that the new symmetrical design of the square completely ignores the two artworks.

Philippe Petit is not an historical figure, however. He is a living French tightrope walker that — on August 8, 1974 — managed to tightrope walk between the two immense towers of the World Trade Center in New York City. After much surreptitious planning and without any prior publicity, Petit performed his precarious act, completely stopping traffic and bringing the commercial bustle of New York momentarily to a standstill.[2] For his effort, Petit was arrested as a criminal.

Before being apprehended by the police, Petit managed to cross between the two Twin Towers a total of seven times upon a thin wire cable. The only thing he had to hold onto during this entire time was his sixmeter long balancing bar.

George Baker, New York, May 1997

Notes

- See Walter Benjamin, "Re the Theory of Knowledge, Theory of Progress," Konvolut N of the PassagenWerk, translated in Gary Smith, ed., Benjamin: Philosophy, Aesthetics, History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1989), p. 49.

- The distance walked by Petit between the World Trade Center Towers measured 39.9 meters; the distance Müller traces between Beuys and De Maria, 32.18 meters.