Installation view of camouflage netting (Chapter 1), façade.

Detail, camouflage netting.

Installation view of loggia where swastika once hung behind Adolf Hitler (see below) that was opened for the first time by Müller following its closure in 1945. Includes laurel trees and flower planters, and photograph of a fashion show at the Export Fair held at the Haus der Kunst in 1946 (Chapter 2), Middle Hall.

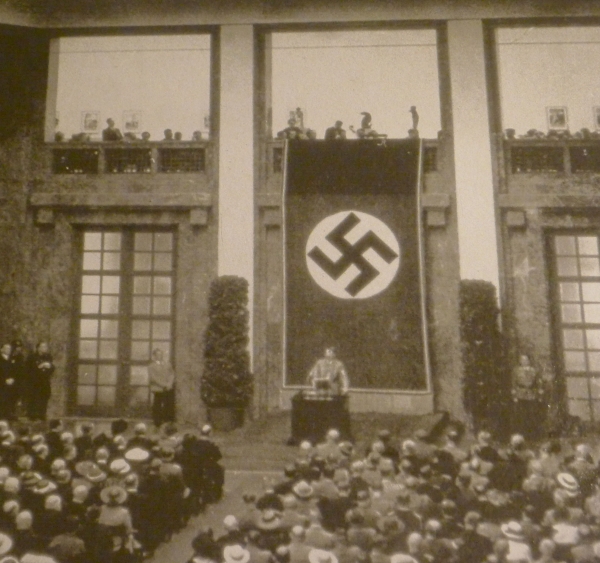

Photograph of Adolf Hitler's speech at the opening of the House of German Art, 18 July 1937.

Installation view of North Gallery staircase with sound collage of historical recordings of the opening of the "House of German Art" with image of Hitler and other Nazi art figures (Chapter 3).

Installation view of the entry to Chapter 4. Film excerpt of the parade of "Golden Days of German Culture" with the model of the "House of German Art" being carried through Munich on 15 October 1933.

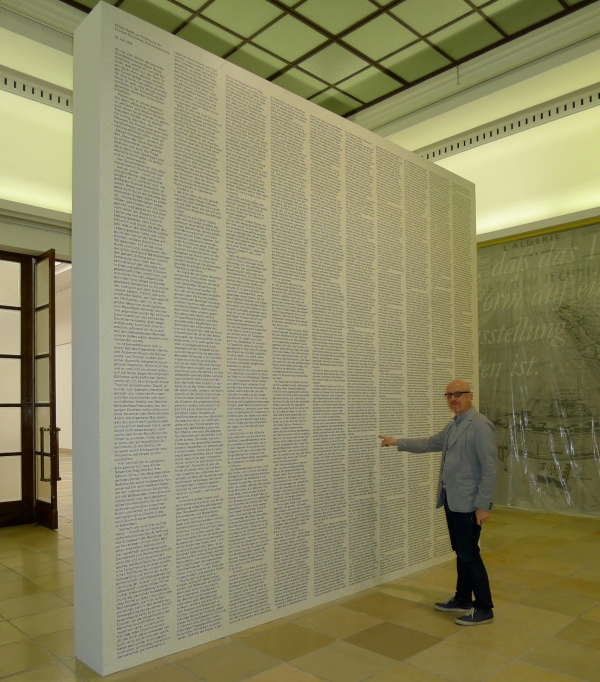

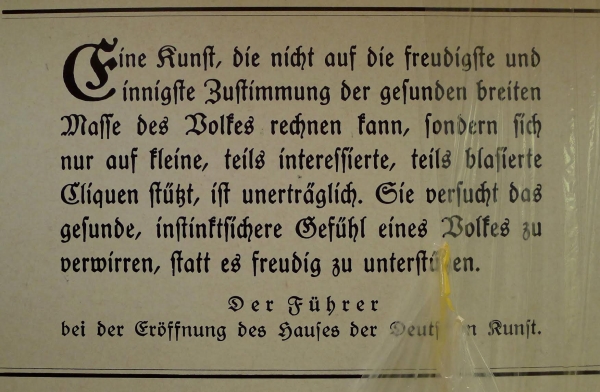

Christian Philipp Müller with text from Hitler's speech at the opening of the building in 1933 (Chapter 4).

White chocolate model of the "House of German Art" at 1:60 scale (Chapter 4) with text from Hitler's speech at the opening of the building in 1933 in the background.

Installation view of North Gallery with wallpaper and guestbook (Chapter 4).

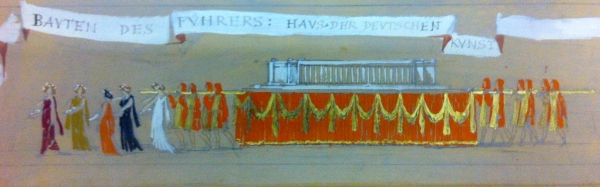

Detail of a painting depicting the model of the Haus der Kunst in a Nazi parade (Chapter 4).

Detail, guestbook (Chapter 4).

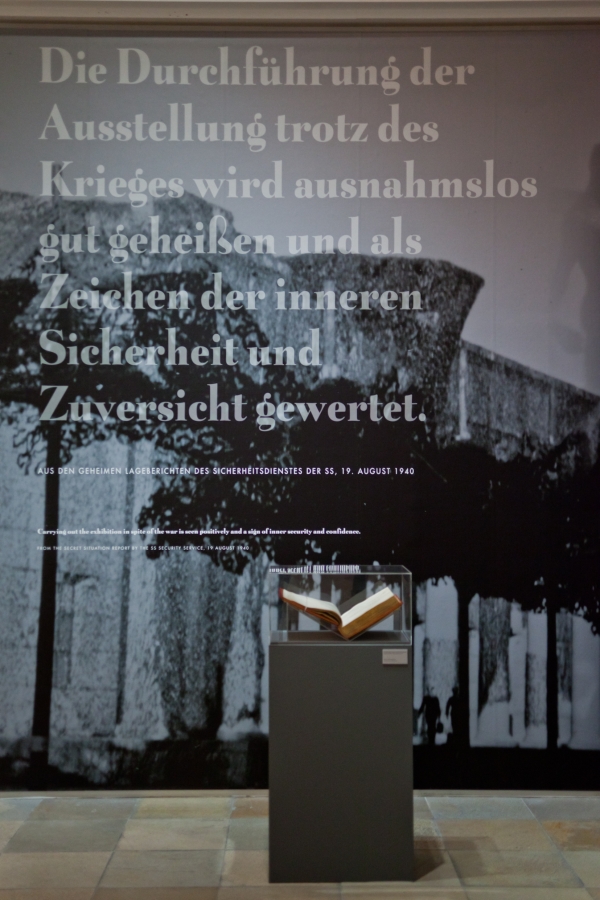

Detail, quote from the Entartete Kunst catalogue (Chapter 4).

Installation view of the entrance to room containing selected artworks from exhibitions at "House of German Art" between 1937 and 1955 (Chapter 5).

Detail of paintings from the "Great German Art Exhibitions" between 1937 and 1945 (Chapter 5).

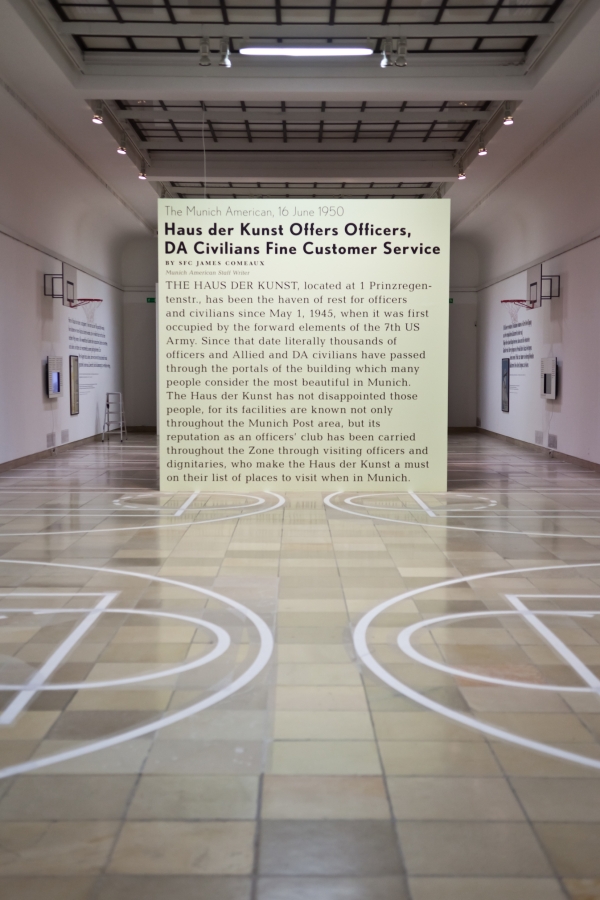

Installation view of the Hall of Honor with basketball court fittings (Chapter 6).

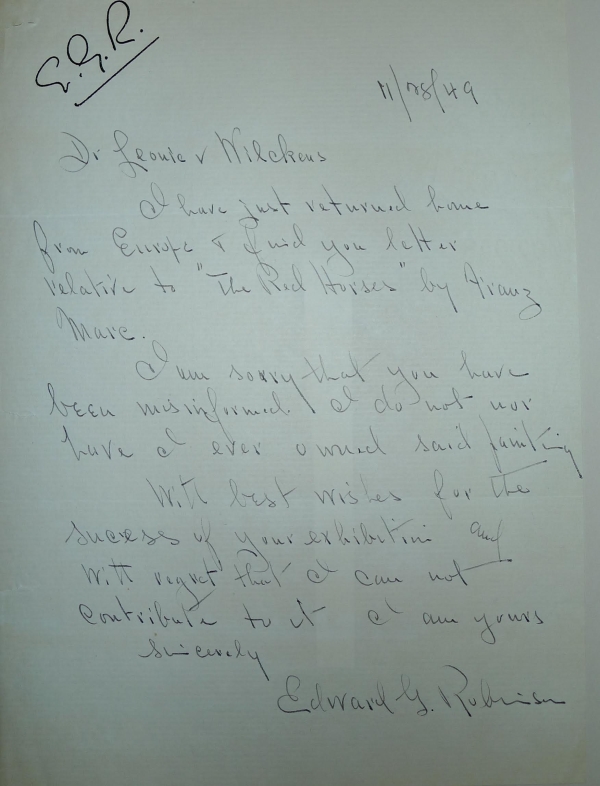

Detail of archival document from the Haus der Kunst: a letter from actor Edward G. Robinson, 28 November 1949 (Chapter 6).

Installation view of archival material and exhibition posters from the building's postwar history (Chapter 6).

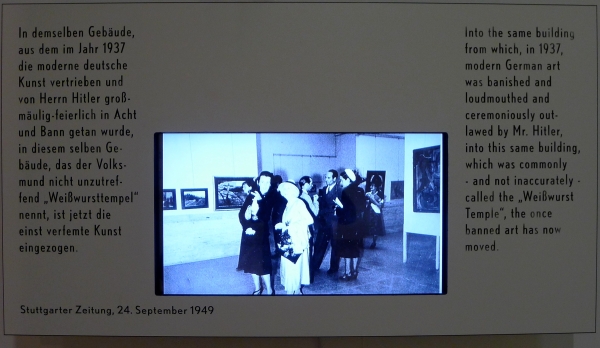

Detail of documentary film from 1945-1955 (Chapter 6).

Histories in Conflict: Haus der Kunst and the Ideological Uses of Art

10 June 2012 – 13 January 2013

Haus der Kunst, Munich, Germany

Exhibition brochure available here.

Exhibition dramaturgy and installations in six chapters.

Elements added by CPM to the frame archival material of the Haus der Kunst:

Chapter 1:

- Camouflage netting on exterior façade.

Chapter 2:

- Blow up of an archival photograph of a 1946 fashion show for the Export Fair at the Haus der Kunst, artificial flowers and (real) laurel trees, and partially opened loggia.

Chapter 3:

- Sound collage of historical recordings of the opening of the "House of German Art" with tinted image under the ceiling of Hitler and other Nazi art figures.

Chapter 4:

- Film excerpt of the parade of "Golden Days of German Culture" with the model of the "House of German Art" being carried through Munich on 15 October 1933.

- Wall text of the entire speech of Hitler at the opening of the building in 1933.

- White chocolate model of the "House of German Art" at 1:60 scale.

- Wallpaper with images and quotes related to the Haus der Kunst during the Nazi era and of the “Entartete Kunst” show.

Chapter 5:

- Storage Display system for a selection of paintings from the "Great German Art Exhibitions" between 1937 and 1945

Chapter 6:

- Basketball court fittings including floor painting, hoops, and nets.

- Archive for letters, exhibition posters, and video documentation from the Haus der Kunst’s postwar history.

© Christian Philipp Mueller for Haus der Kunst, Munich, 2012

Museum as Archive: Christian Philippe Müller’s Dramaturgy for “Histories in Conflict: Haus der Kunst and the Ideological Uses of Art, 1937-1955”

At a conference on museums in 2011, Manuel Borja-Villel, director of the Museo Reina Sofía, addressed the fraught relationship between a museum’s architecture and the artworks it holds inside, as described by Rosalind Krauss in her essay “The Cultural Logic of the Late Capitalist Museum” (1990). [1] He proposed a new approach to exhibiting art that he described as “the archival commons,” in which museums foster communal spaces for engaging with history and culture through oral histories, micronarratives, and dispersed subjectivities. [2]

Similarly, in her book Radical Museology: Or What's Contemporary in Museums of Contemporary Art? (2014), Claire Bishop examined the radical strategies that innovative art museums have used in their shift away from the “nineteenth-century model of the museum as a patrician institution of elite culture to its current incarnation as a populist temple of leisure and entertainment.” [3] She argued that museums with historical collections have increasingly proven to be productive testing sites for a kind of “non-presentist, multi-temporal contemporaneity” that acknowledge and navigate hybrid temporalities in ways that are politically driven. [4]

Perhaps one of the best recent examples of the types of strategies outlined by Borja-Villel and Bishop is Christian Philipp Müller’s 2012 intervention in the exhibition “Histories in Conflict: Haus der Kunst and the Ideological Uses of Art, 1937-1955,” held at the Haus der Kunst, Munich, and curated by archivist Sabine Brantl and curator Ulrich Wilmes in collaboration with Director Okwui Enwezor. Organized on the occasion of the museum’s 75th anniversary, Müller was invited to create a “dramaturgy” for the exhibition that would narrate the history of the institution’s cultural policies from its inception under the Nazis in 1937 until 1955, the year of the first documenta in Kassel.

Müller and Enwezor employed the term “dramaturgy,” usually associated with theater, to describe Müller’s shaping of the museum’s historical narrative, which he accomplished by working closely with Brantl in the museum’s archives. Müller’s interventions — which ranged from photographic and multimedia installations to archival displays and exhibition designs — helped to bring these archives to life, translating them into a legible representation of the museum’s ideological purposes throughout its history for contemporary audiences. Originally built as a “House of German Art,” the building was viewed as the successor to Munich’s glass and iron Glaspalast (Glass Palace), which was modeled on London’s Crystal Palace and destroyed in a fire in 1931. The Haus der Kunst was built between 1933 and 1937 by Hitler’s favorite architect, Paul Troost. Its imposing neoclassical design was inevitably conceived to embody and communicate the fascist ideals of National Socialism, the legacy of which the institution grapples with to this day.

Organized into six chapters, Müller’s dramaturgy outlines key moments in the building’s history by underscoring its shifting ideological purposes over time. Effectively putting the building itself on display, he worked spatially from the outside in (starting with the façade), rather than strictly chronologically, as he charted the museum’s inception in 1937 to its postwar manifestations as an U.S. military officer’s club and an exhibition hall displaying the same modern art its founders disavowed.

In “Chapter 1 (Façade)” Müller takes the grand edifice of the museum as his subject by recreating the camouflaged nets draped on the structure in 1942 to disguise and protect it from aerial bombings of the city by Allied forces. Yet, instead of making the building disappear, Müller’s camouflaged netting, executed in vibrant fuchsias and tangerines, instead “intensif[ied] the visual presence of the building.” [5] By “putting the building in drag,” he undermined the use and symbolism of the original netting — militarism, conformity, and concealment — with a vociferous endorsement of subaltern nonconformity. [6] Müller’s pink camouflage netting can be read as a “queering” of the façade, an intervention that manifested what Carolyn Dinshaw has described as “an expanded range of temporal experiences … [which] require a rewiring of the senses.” [7] It is this sensational affective experience that beckoned the viewer to step inside and that oriented her to the hybrid temporalities and subject positions Müller’s dramaturgy engendered once there.

Upon entering the building’s central hall, the viewer encountered “Chapter Two (Middle Hall).” Formerly known as the “Hall of Honor,” the Middle Hall was the location of the openings of the “Great German Art Exhibitions” held from 1937 to 1944. It was at these events that the Nazi leadership gathered annually, and where Hitler first declared a “relentless cleansing war” against modernism. [8] In the 1950s, as part of a “de-Nazification” effort, architectural modifications were made to this space to erase the memory of its prior use by the Nazis. [9] According to archivist and co-curator Sabine Brantl, after the war Germans were eager to forget the horrors of the recent past. [10] In 2003, then-Director Chris Dercon initiated the “Critical Reconstruction” project, aimed at reckoning more directly with this difficult legacy by gradually exposing the building’s original architecture in order to make its history more transparent. [11]

Responding to this fraught history of the space, Müller focused his attention on the rectangular niche framed by red travertine marble molding in the hall’s north wall, where a large draped swastika and symmetrical laurel bushes surrounded Hitler’s podium during annual Nazi gatherings. In place of the podium, Müller framed an oversized color-tinted black and white photograph from the archives documenting a fashion show from the Export Fair held in the Haus in 1946, one year after the war had ended. Depicting a runway model in 1940s-era fashions before a seated crowd, the image occupied the space where the rectangular Nazi flag once hung. As in the original configuration, two planted laurel trees flanked the image. However, Müller also included a new addition — a flower box of pink and red blossoms — placed underneath the image as a gendered response to the hyper-rationalist, macho aesthetic of the spectacular fascist displays. Through Müller’s “feminizing” of the space, which recalls the “Hollywood flair” of the period, he exposes the cinematic fantasy and desire for romantic escape in the German imaginary of the early postwar period. [12]

Following the Middle Hall, “Chapter 3 (Staircase)” was situated in the stairwell leading up to the exhibition spaces in the North Gallery where Chapters 4, 5, and 6 of the exhibition were housed. Here, Müller installed a sound collage of historical recordings of the media spectacle surrounding the laying of the building’s foundation on 15 October 1933, one day after Germany withdrew from the League of Nations. [13] In the skylight above the staircase, Müller placed a translucent sepia-tone photograph from the archives depicting a group of men chatting around a table on the museum’s terrace. This scene epitomizes the values of bourgeois leisure associated with 19th and early 20th century museum-going. However, upon closer inspection, one realizes it actually depicts Hitler and other players in the history of Nazi art policy on the eve of the museum’s opening in 1937.

“Chapter 4” displayed photographs, texts, and other records that documented the museum’s history from its inception through the end of the war. The archival images were integrated into the architecture of the gallery through larger-than-life-size reproductions printed onto the walls, superimposed with text from archival documents. For instance, one of Hitler’s speeches was printed on a partition several meters high, causing viewers to experience its presence physically before considering its content. [14] A film was projected on the opposite side of the wall, depicting a procession that occurred on the day of the laying of the building’s foundation, in which 18 men dressed in medieval clothing carried a model of the building. The nine-meter-long model became a notorious cult object that the regime exploited for propagandistic purposes. It was displayed on a number of occasions including the “2000 Years of German Culture” pageants held between 1937 and 1939 and the World’s Fair in Paris in 1937. Top Nazi military leader Hermann Goering even gave a gold replica of the model to Hitler on his 50th birthday in 1939. [15] Müller responded to these traditions by putting his own model of the building on display, but instead of gold, it was composed of decadent white chocolate, an allusion to the seductive power of Nazi ideology in the 1930s. [16]

“Chapter 5” of the exhibition put artworks on display that were shown in the museum between 1937 and 1955, side by side with those shown in the infamous 1937 “Entartete Kunst” (Degenerate Art) Exhibition of disavowed avant-garde and modernist art organized by Joseph Goebbels and presented in the nearby Hofgarten gallery in Munich. The result was the juxtaposition of conservative social realism, the bread and butter of Nazi artistic taste, with the radical art of Beckmann, Dix, Kandinsky, Kirchner, and Klee, among others. Yet, in at least one case, the distinction between “German” art and “degenerate” art was not so clear: two of Rudolf Belling’s abstract sculptures were presented in the Degenerate Art Exhibition at the same time that his naturalistic portrayal of a boxer was on view in the “House of German Art.” [17] The museum storage racks onto which the paintings were affixed allowed viewers to see the personal notes and other provenance information that further helped to deconstruct the ideological values informing them.

“Chapter 6,” the narrative’s dénouement, addressed the period after the collapse of the Third Reich and the liberation of Munich by U.S. troops in 1945. The U.S. military seized control of the building and established an officer’s club replete with a restaurant, dance hall, shops, and even a basketball court, which Müller referenced by adding hoops and re-drawing the court’s lines on the gallery’s floor. At the same time, the building hosted industrial and commercial trade fairs, as well as historical art exhibitions, which were staged in the museum’s West Wing as early as 1946. By midcentury, the museum finally embraced the modernist art that it had once so vehemently rejected, with exhibitions such as “The Blue Rider” (1949), “Painters at the Bauhaus” (1950), and a Picasso retrospective featuring “Guernica” (1937) in 1955. [18]

Weaving in and out of past and present, and touching on multiple points along the timeline in between, Müller’s interventions created an alternate timescape that epitomized Enwezor’s call to “think historically about the present, since the present is always embedded in the past.” [19] According to Boris Groys, while art museums have traditionally “functioned as a paradoxical archive of eternal presence,” today artists and curators have begun to “shape museum spaces … into an archive of artistic documentation” that transforms our relationship to past and present. [20] Müller’s sensitive and insightful navigation of multiple and hybrid temporalities and his foregrounding of multivalent subjectivities epitomized Bishop’s claim that museums should offer us “a space to reflect and debate our values [without which] there can be no considered movement forward.” [21] Through his dramaturgy, Müller insisted that the Haus der Kunst’s past offered a pressing and urgent relevance to the present.

Text by Gillian Sneed

Footnotes:

- The conference was titled “The Now Museum: Contemporary Art, Curating Histories, Alternative Models” and was held at the New Museum, New York from March 10–13, 2011. See Rosalind Krauss, “The Cultural Logic of the Late Capitalist Museum,” October 54 (Fall 1990): 3-17.

- See Gillian Sneed, “Now or Newer” Art in America online, March 21, 2011. Accessed March 5, 2016. http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-features/news/now-museum-new-museum/ Art in America.

- Claire Bishop, Radical Museology: Or, What's ‘Contemporary’ in Museums of Contemporary Art? (London: Koenig, 2014), 5.

- Bishop, Radical Museology, 23, 27.

- Haus der Kunst, “Histories in Conflict,” exhibition brochure, n.p.

- Statement by the artist in conversation with the author, Brooklyn, NY, January 2016.

- Carolyn Dinshaw, et al., “Theorizing Queer Temporalities: A Roundtable Discussion,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 13, nos. 2-3 (2007): 178.

- Haus der Kunst, “Histories in Conflict,” exhibition brochure, n.p.

- Ibid.

- Birgit Görtz, “When Hitler Defined Art,” Deutsche Welle (DW), Art Section, July 19, 2012. Accessed March 5, 2016. http://www.dw.com/en/when-hitler-defined-art/a-16033874.

- See “Exhibition Documentation 2000-2009,” Haus der Kunst website, accessed March 5, 2016, http://www.hausderkunst.de/en/research/documentation/exhibition-documentation/2000-2009/; and “Critical Reconstruction,” Haus der Kunst website, accessed March 5, 2016. http://www.hausderkunst.de/en/research/history/historical-documentation/critical-reconstruction/.

- Haus der Kunst, “Histories in Conflict,” exhibition brochure, n.p.

- Ibid.

- Michael Schleicher, “Deutsche WelleHaus der Kunst: Geschichtsbewusst mit Schokolade,” Merkur, Kultur Section, June 8, 2012. Accessed March 6, 2016. http://www.merkur.de/kultur/haus-kunst-geschichtsbewusst-schokolade-2348082.html.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Haus der Kunst, “Histories in Conflict,” exhibition brochure, n.p.

- Ibid.

- Okwui Enwezor quoted in Görtz, “When Hitler Defined Art.”

- Boris Groys, “Multiple Authorship,” IDEA artâ + societate 26 (2007): n.p. Accessed March 5, 2016. http://idea.ro/revista/?q=en/node/41&articol=469.

- Bishop, Radical Museology, 61.