Detail, “Illegal Border Crossing between Austria and the Principality of Liechtenstein,” 1993/2005, still.

Detail, “Illegal Border Crossing of the Austrian-German Border with Philip Hämmerle,” 1993

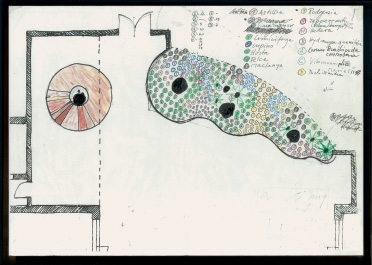

Sketch for the newly landscaped sculpture courtyard, Austrian Pavilion, 45th Biennale di Venezia, 1993.

“Orangery” of the North, Austrian Pavilion, 45th Biennale di Venezia, 1993.

Garden table, Austrian Pavilion, 45th Biennale di Venezia, 1993.

Removed garden wall and newly landscaped sculpture courtyard, Austrian Pavilion, 45th Biennale di Venezia, 1993.

Woodcut from the Kronprinzenwerk, 1895, Austrian Pavilion, 45th Biennale di Venezia, 1993.

Installation view, “Project Migration,” Cologne Kunstverein, 2005.

Green Border, 1993 (impressions, no audio)

Green Border

In: Austrian Pavilion, 45th Biennale di Venezia

14 June – 10 October 1993

Stellvertreter/Representatives/Rappresentanti

(with Andrea Fraser, Gerwald Rockenschaub)

Sculpture Courtyard:

– “Gartentisch,” 1993, different kinds of wood corresponding to the percentage of various types of trees in Austria, turnable; diameter: 157 inches, Collection of Günther Lorenz

– Demolition of the garden wall and redesign

– Two signs with botanical information

Right Wing:

– Outside: surveillance camera

– Inside: eight trees from Austria, eight signs with botanical and geo-political information, eight plaques with directions, eight veduta from the Austrian National Library, air conditioner with sluice and monitor

For the 45th Venice Biennale in 1993, commissioner Peter Weibel invited Austrian artist Gerwald Rockenschaub to exhibit in the Austrian pavilion, proposing collaboration with non-Austrian artists as well. The invitations issued to Andrea Fraser (USA) and Christian Philipp Müller (Switzerland) broke the tradition of national competition that had been the guiding principle of the Venice Biennale since 1895. Rockenschaub occupied the central room of the pavilion and made this location the subject of his work; Müller and Fraser took the side wings. Fraser’s theme was the occasion, the Biennale itself, while Müller’s was the patron, the Austrian state.

Controversy arose in the Austrian press even before the exhibition, concerning the participants’ ostensible threat to national identity. In reaction, the poster for the exhibition showed the three artists in folkloric costume at the table of a stereotypical Austrian pub. In the catalogue for the pavilion, Weibel and others, including Slavoj Zizek, Chantal Mouffe, and Helmut Draxler wrote critical essays on the principle of nationalism and its Austrian history.

These issues are also manifested in the pavilion itself. The building was constructed in 1934 after plans by Josef Hoffmann, although Hoffmann’s intent of completely enclosing the Austrian area with a high wall was not carried out. At the time of the 21st Biennale in 1938, Austria had been annexed by Nazi Germany and was thus associated with the German pavilion as the “Ostmark.” In 1954, Hoffmann’s building was opened toward the group of trees lying behind it. The garden received an asymmetrical enclosure typical of the time, shifting the building out of its previously absolute symmetry.

On his first visit in 1992, Müller found the enclosed area completely overgrown. At the left end of the garden, a double door (an emergency exit) led into the no-man’s-land between the pavilion and the barbed-wire enclosure of the “Giardini.” Müller had this garden wall completely demolished, removed the underbrush, and replanted the area, thereby opening up the view.

Müller’s “Green Border” operates on four levels: as a national boundary separating Austria from neighboring countries: as a historical border shift on the map of Austria, as an architectural boundary separating the Austrian pavilion from the overgrown terrain behind it, and finally, as a reinstallation of the biological and geopolitical features of the green borders in the side-wing of the pavilion.

Dressed as a hiker, Müller followed Austria’s green borders, exploring their function as barriers to the former Eastern-block countries of the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, and Slovenia as well as to the western states of Italy, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and Germany. He sought out wooded border regions and here crossed national boundaries. While crossing to the Czech Republic, he and his assistant were arrested and prohibited from reentering the country for three years. At each border crossing, Müller sent postcards to friends and art dealers inscribed with a sentence inspired by On Kawara: “I crossed the border between X and Y and I AM STILL ALIVE.”

At the Biennale, Müller transposed the green border into the right-hand wing of the pavilion. As visitors passed through a swinging plastic door, the climate immediately changed: an air conditioning system installed over the door enabled Müller to maintain an ideal conservatorial temperature. A security monitor provided a direct view into the landscape while a camera mounted on the exterior of the pavilion provided surveillance of the green border of the grounds. On the right-hand wall were eight landscape drawings, preliminary studies for woodcut prints. They represent regions now located on the borders of Austria, sites immortalized in woodcut in the Kronprinzenwerk, an Austro-Hungarian encyclopedia of 1895. The eight studies displayed by Müller showed views of the eight green borders over which he had crossed. Plexiglas panels mounted beneath the drawings provided documentation of the border crossings in German, English, and Italian, while across from them eight trees typical of each of the landscapes formed an “orangery” of the North. Brought in from Austria, they were planted in terra cotta pots from the Giardini and equipped with signs giving information on their botanical as well as geo-political origin. Müller continued this reconstruction of the green borders at the edges of the enclosure — on the one hand, by replanting the garden area within the torn-down wall, and on the other, by means of a round, revolving table four meters in diameter, enclosing a tree and a column. It was installed in the asymmetrical addition to the enclosure from 1954 and was made of the thirteen most common types of wood in Austria. The table was used for the display of merchandise designed by Fraser, Rockenschaub, and Müller.

Essay by Alexander Alberro available here.