Eine Welt für sich

22 September – 31 October 1999

Schleifmühlgasse, Vienna

Three-part installation

Part 1:

Coffeehouse with reading material on the Freihausviertel

Part 2:

Temporary museum with loans from institutions and private individuals in the Freihausviertel

– Various objects, cordon, labeling, light switch, light bulb, four loudspeakers

– "Eine Welt für sich" (cooperation with ORF-Kunstradio), 1999, CD, 59 min. <a href=\"index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=35&Itemid=66\">

Part 3:

Historic archive with documents from residents of the Freihausviertel

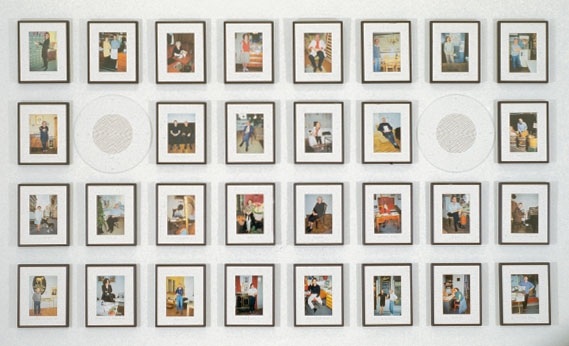

– "Eine Welt für sich," 1999, 30 photographs, passe-partout, framed; each 11 x 9 inches; courtesy Georg Kargl, Vienna

The project around the Freihaus district was a snapshot of the Freihausviertel in Vienna through the eyes of its inhabitants. In order to make the identity of the neighborhood visible through its disparate elements, Müller used an empty café-bar to construct a portrait of the Freihausviertel using a literature café, a CD audio drama and radio feature, topographic documentation, a catalogue, and an installation made out of objects on loan.

Spanned across the three windows of the temporary exhibition space, the title of the exhibition announced the program: “Eine Welt für sich,” an open, light-filled café and reading room, visible from outside, where literature on the history of Vienna, its neighborhoods, and the Freihausviertel in particular, provided an entry into the exhibition. This was supplemented by a wall display illustrating the historical topography of the area including preserved depictions of the eponymous Freihaus, a huge residential complex in the Viennese neighborhood of Wieden (now only visible in fragments), and photographic portraits of the neighborhood residents Müller interviewed. For over 300 years, Freihaus was a city within a city, with six courtyards and 21 stairwells. Its own jurisdiction system and church protected Freihaus from without. Beginning in 1913, Freihaus was demolished in successive stages. Following World War II, what remained had to be torn down due to extensive bombing damage. Today, the Freihaus is more of a memory than a real presence. It is this memory that Müller pursued through the exhibition.

Tucked away in the back area of the former office of Austrian winegrowers was the entrance to the darkened exhibition space, its display windows covered with black film. Here, fragments of the remembered history of the Freihausviertel, compiled with the help of residents, were on view. From outside, one could only see the oversized photograph of a lit, hanging light bulb. Inside, the multiple layers of local history were lit with bright light within an area cordoned off by illuminated steel guardrails. In this space, Müller presented objects that he had received as loans from people he interviewed, exhibition items corresponding to the stories they told. Müller translated the fragmentary memories of the neighborhood residents — who added their personal interests and affects to the constructed identity of the “Freihaus” label — into an installation, a historical museum dedicated to the history that unfolded through “Eine Welt für sich.” Here too, Müller emphasized the differences, not the similarities, among the contributions to this repository. The objects residents loaned: a harp, a hatter’s tool, a costume from the first on-site performance of Mozart’s “The Magic Flute,” a soup tureen, and a glass of pickles were separated from each other, and installed on varying pedestals. The room was flooded in complete darkness, and it was only possible to view the exhibition selectively. The viewer had to turn on a light switch, which only lit one of the objects, so that the impressions and contributions were isolated from one another. Also, the process leading up to the collection of objects was represented in the exhibition space in the form of a radio play, which was composed of the interviews Müller had conducted in May 1999 with thirty inhabitants, business people, and resident institutions of the fourth Viennese district — and then turned into a radio feature and CD. Müller posed questions about the history of the Freihaus and the district, and in this oral form of history, he discovered subjective variations, corrections, and shifts in written historical accounts. Sabine Breitwieser of the Generali Foundation and Georg Kargl of Galerie Kargl had their say, as did the sign manufacturer Josef Samuel and residents from the neighborhood.

In the criss-crossing stories of back rooms, prostitution, Marx, Lasalle, and even those on the filming of My Fair Lady, a rich texture of rupture and difference unfolds within the presumed “Freihausviertel” image. The shared identity was encouraged by the business people of the neighborhood, among others, who founded the IG Kaufleute Freihausviertel (Freihaus Business Interest Group) in 1998, a syndicate for the creation of a product-like collective identity. Müller had been invited by this interest group to develop his project about the Freihausviertel, and he, the artist, who himself had become an element of this business idea, inverted the historicizing identity construct of the group. His work placed difference in the foreground, the historical projections of the individual, and the specific interests that determined them.

Essay by Alexander Alberro available here.