Installation view, Galerie Christian Nagel, Berlin.

Interior view, “My BMW,” 2005; Poplar plywood (MDF coated), white paint, silkscreen, 90 x 34 x 24 inches

“Schön, wenn immer jemand für einen da ist,” 2005; Silkscreen on passé-partout cardboard, 55.1 x 39.4 inches

Interior view, “My Porsche,” 2005; Poplar plywood (MDF coated), white paint, silkscreen, 90 x 34 x 24 inches

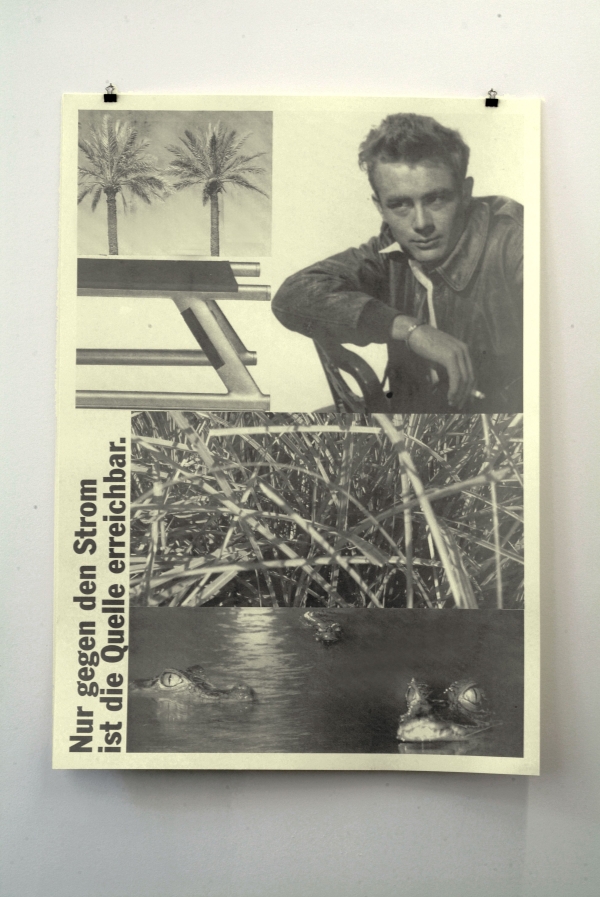

“Nur gegen den Strom ist die Quelle erreichbar,” 2005; Silkscreen on passé-partout cardboard, 55.1 x 39.4 inches

Berlin, Deutschland und die Welt

17 September – 5 November 2005

Galerie Christian Nagel, Berlin

- “My Mercedes,” 2005; Poplar plywood (MDF coated), white paint, silkscreen, 90 x 34 x 24 inches.

- “My BMW,” 2005; Poplar plywood (MDF coated), white paint, silkscreen, 90 x 34 x 24 inches.

- “My Porsche,” 2005; Poplar plywood (MDF coated), white paint, silkscreen, 90 x 34 x 24 inches

- “Die erste Berührung werden Sie nie vergessen,” 2005; Silkscreen on passé-partout cardboard, 55.1 x 39.4 inches. 1/5 Kulturstiftung des Freistaates Sachsen; 2/5 Birgit Steenholdt-Schütt.

- “B-flexible B-unique B-happy,” 2005; Silkscreen on passé-partout cardboard, 55.1 x 39.4 inches. 1/5 Birgit Steenholdt-Schütt; 2/5 Ljuba Berankova.

- “Nur gegen den Strom ist die Quelle erreichbar,” 2005; Silkscreen on passé-partout cardboard, 55.1 x 39.4 inches. 1/5 Hertingk Diefenbach; 2/5 Bleibtreu Galerie GmbH; 3/5 Kulturstiftung des Freistaates Sachsen.

- “Schön, wenn immer jemand für einen da ist,” 2005; Silkscreen on passé-partout cardboard, 55.1 x 39.4 inches. 1/5 Steenholdt-Schütt.

For this installation, Müller was inspired by B. Joseph Pine II and James H. Gilmore’s book The Experience Economy (1999), which explored the methods modern companies use to design memorable events for customers. A business model that followed the “service economy” of earlier eras, successful businesses of the “experience economy” use goods and services as theater props to enhance customers’ moods, thereby increasing their desire and willingness to pay more for the extra experience.

The artist investigated the theatricality of these experiences using luxury automobiles as a case study. He visited automobile exhibition showrooms, went on tours of factories, and conducted interviews with employees of the major car manufacturers in Germany: BMW, Mercedes, Porsche, and VW. There, he looked at the “experiences” that made up each brand. For instance, at BMW’s plant in Leipzig, workers wear asymmetrical overalls designed by the late Zaha Hadid and the robots that assemble the cars dance with people, transforming the factory line into a theater-like spectacle. In addition, the companies often commission world-renowned “starchitects” like Hadid to design their amusement-park-style buildings, which further increases the value of the brand.

For the central space of the gallery, Müller created three white cubes, the interior of which are silkscreened with images taken from his visits to these factories in bold monochrome hues. The appearance of the sculptures follows Le Corbusier’s Modulor, an anthropometric scale of proportions based on an “ideal man” of 1.83 meters tall. The size of Müller’s structures, as well as the openings that provide views of the interior, are in accordance with Le Corbusier’s measurements, but with an ironic twist. While the architect thought his scale would unfailingly produce aesthetically pleasing products, Müller’s sculptures fragment the viewer’s body upon entry, breaking it down into car-like parts.

These sculptures create an experience for Müller’s viewers that is designed to deconstruct the gaze: when seen from the interior, viewers have intimate experience resembling the private moments spent inside a vehicle or with a work of art in one’s own collection. When seen from the exterior, however, the utopian purity of the structure is tarnished. Viewers within the gallery space are excluded from the private experience of those on the interior, mimicking the exclusion of the art world or even those able to purchase a luxury car.

The four poster-size collages found on the gallery walls combine photographs taken by the artist at the factories and texts derived from their advertisements in monochrome metallic shades similar to car finishes. By evoking a sensorial experience, the artist demonstrates how a PR company might construct an marketing campaign based on a slogan like BMW’s “Schön, wenn immer jemand für einen da ist” (It’s great if someone is always there for you), which emphasizes the security of BMW’s vehicles to assuage risk-adverse customers. Müller’s silkscreen includes images associated with safe risk-taking such as a fledgling falcon embarking on its first flight and families on an Oktoberfest amusement park ride. The sleek architecture of the BMW “Welt” in Munich evokes the texture and tactile quality of a new car, while the handcuffs refer to the vehicles as fetish items. Müller also counters claims of environmental sustainability with the image of the falcon, which the BMW company intentionally nests on along the rooftop of Hadid’s design.

“Berlin, Deutschland und die Welt” is connected to Müller’s previous installation “The Sweetest Place on Earth” (2002) at Galerie Christian Nagel in Cologne and “Branding the Campus” (1998–ongoing) at the Universität Lüneburg. The first of these installations concerned the American town of Hershey, Pennsylvania, the identity of which – just like the identity of VW in Wolfsburg – is based on the products of one single company, whereas the second installation re-interprets the theme of branding in an academic setting.

Text by Cara Jordan