Installation view, Museum für Gegenwartskunst Basel

Installation detail, “Untitled,” 2007

Christian Philipp Müller at the Basler Papiermühle, Basel

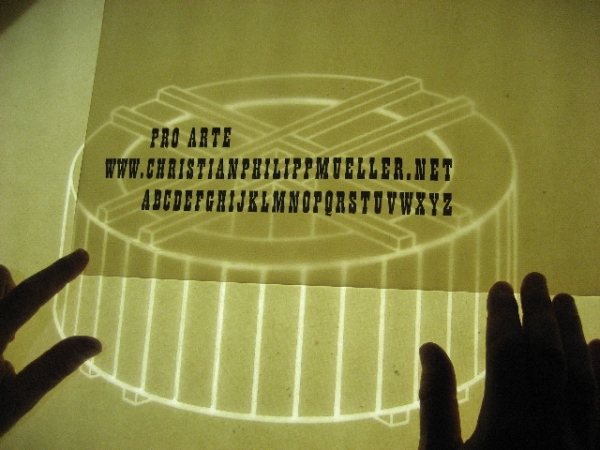

Waterwheel at the Basler Papiermühle, Basel

Detail, handmade paper with watermark

Basics

19 January – 15 April 2007

Museum für Gegenwartskunst Basel and Basler Papiermühle, Basel

- Wasserrad (waterwheel), 2007, wood, metal, diameter,

189 x 70.9 inches

- Wäschekorb (laundry basket), 2007, wicker and cotton,

43.3 x 23.6 inches

- Inventar (inventory), 2007, 4193 books, Papiermühle Basel library, 79 A4-laser printouts

- Wasserbar (water bar), 2007, 3 glass carafes and 12 glasses, rack, 78.7 x 11.8 inches

- Untitled, 2007, three sheets of paper, hand made with water mark, silkscreen, 19.7 x 27.6 inches

For his “Basics” exhibition at the Museum für Gegenwartskunst Basel, Christian Philipp Müller decided to explore the historic production sites of the St.-Alban-Tal (Valley of St. Alban) and to view these in relation to his own history.

The medieval St.-Alban-Tal in Basel, Switzerland’s largest contiguous area ever to be earmarked for urban renewal, was so comprehensively restored between 1974 and 1987 that it has since become an urban idyll. Two new museums were built close to each other, the Basler Papiermühle (Basel Paper Mill) and the Museum für Gegenwartskunst (Museum for Contemporary Art), the aim being to attract more people to what had been a relatively unfrequented part of town. Starting in the Middle Ages, St.-Alban-Tal once had a thriving paper-making industry. Indeed, one main reason for Basel’s ascendancy as a center of humanism in the days of Hans Holbein the Younger, Erasmus of Rotterdam and others, was the presence of countless quality book printers — all of whom required paper. In the following centuries, the importance of the paper mills dwindled. Large volumes of water were used as drinking water for a population that had doubled by the early nineteenth century. In yet another reversal of fortune, a spring once deemed worthy of mention in travel guides today supplies water to the air-conditioning system of the Museum für Gegenwartskunst. When it opened in 1980, this museum was the first of its kind in Europe. It consists of two buildings: a nineteenth-century factory building that once belonged to the Papierfabrik Stöcklin, and a new building designed by the architects Wilfried and Katharina Steib.

The history of the St.-Alban-Tal, including its facelift in the late nineteen-seventies and early nineteen-eighties, tells us about the now obsolete economy of the age of Gutenberg, and also how that same economy has since metamorphosed into modern cultural institutions. This history, in relation to his own as a typesetter, provides the starting point for Müller’s exploration in “Basics.” Upon entering the Museum für Gegenwartskunst, visitors first encounter Müller’s very own framed Gautschbrief of 1977. This Gautschbrief is documentary evidence of his having completed his apprenticeship as a typesetter and of having undergone the journeyman’s initiation ritual, which traditionally involved ducking.

In the gallery space, a large wicker laundry basket can be seen, which can also be found in the neighboring paper museum. This basket was used to collect rags for paper-making. Cotton rags were once in short supply — unlike today, when vast quantities of unwanted clothes are discarded and collected every year. Although cotton rags are now used only for exclusive paper, such as those to make banknotes, visitors to the exhibition will be invited to contribute their own “rags.” After being sorted and cleaned, these garments made of white cotton and linen will end up in a basket. The artist will then use them to make his own handmade paper that will bear his own specially designed watermark. On the rear wall, meanwhile, there is a “Water Bar” and twelve glasses containing fresh water from the King David Fountain on the swanky St.-Alban-Vorstadt — the same spring that now supplies water to the museum’s air-conditioning system. The opposite wall features a seventy-nine-page list of all 4,193 publications on the theme of paper-making listed in the catalogue of the Swiss Paper Museum, while the third wall displays a large-format plan of the many canals and conduits of the St.-Alban-Tal. The installation’s centerpiece, however, is a new waterwheel, forcibly cut-off from its functional context, which is, of course, the generation of energy. This wheel is a copy of the romantic, moss-clad 1980 “original” that now drives the mill of the paper museum. What unites the redundant waterwheel with other constituent parts of this new, site-specific installation and its relation to Marcel Duchamp’s “Large Glass” is its concern with the transformation of history, value and context.

Taking the St.-Alban-Tal as his starting point, Müller has created a reflective sculpture that works on both a micro- and macrocosmic level. The divarication so often inherent in his installations is rendered visible here not only through his inclusion of the water grid plans in the St.-Alban-Tal, but also through the cycle of water usage, from the symbolic act of baptism to water as a source of energy, as the provider of wellness, as drinking water, and as a means of maintaining an artificial climate inside the museum. His involvement of several institutions based there also renders them visible.

In addition to the Swiss Paper Museum, Müller realized a related project for the neighboring [plug.in] Forum for New Media, an installation consisting of obsolete computers. This work exposes the extent to which the digital age is built on planned obsolescence and is still dependent on the old medium of paper. The institutional white cube of the Museum für Gegenwartskunst appears to have become porous. As part of the show, Müller offered guided tours of the local canals and conduits. The diverse institutions based in the St.-Alban-Tal thus became permeable entities, defined primarily by the exchange taking place between the interior and exterior.