Installation view, room 389 with 47 acoustic studies framed at right and sound proofing curtains at rear.

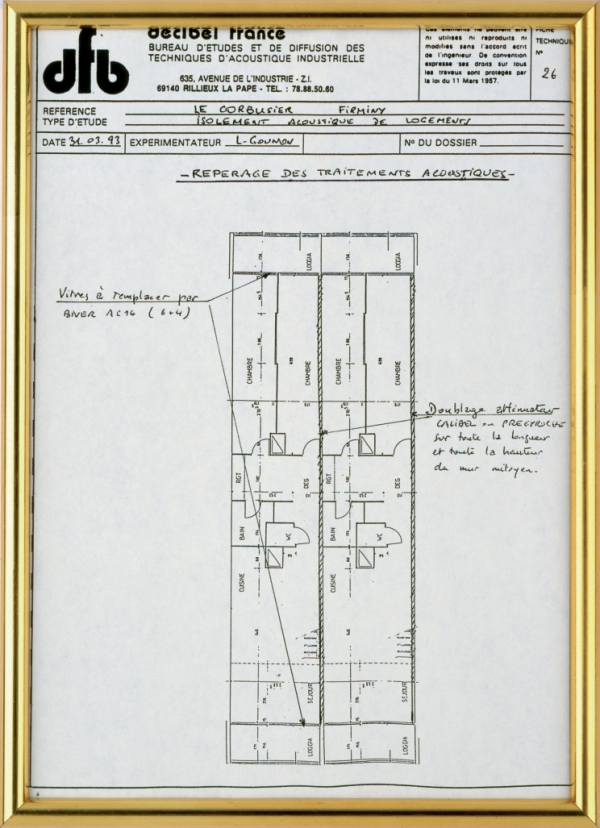

Detail, acoustic study.

Detail, sound proofing curtain.

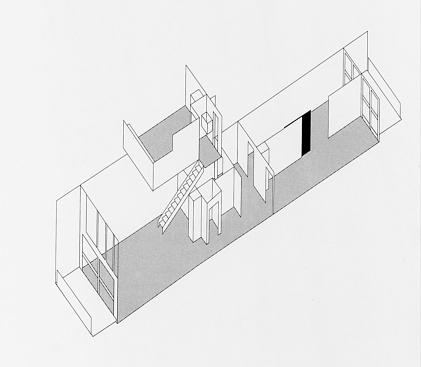

Architectural drawing of an apartment in the Unité d’Habitation.

Common view of an apartment in the Unité d’Habitation.

Le Corbusier, Maison de la Culture et Communication, stadium, 1968.

Foundation stone of the church of St. Pierre in Firminy.

Individual Comfort

1 June – 30 September 1993

Project Unité, Unité d’Habitation, Firminy, France

Apartment 389

– “Individual Comfort,” 1993, acoustic study (47 elements), framed; sound proofing curtains, neon tubes, wall painting; Sammlung Karola Kraus

Located near Saint-Étienne in southeastern France, Firminy was an exclusively industrial city into the nineteen-eighties, its architecture determined by the needs of early capitalist mass production. In 1954, Le Corbusier was commissioned by then Mayor Eugène Claudius-Petit to create an architectural center for the city, which had already been restructured in the preceding years. Le Corbusier translated a concept from ancient Greek urbanism into the twentieth century by superimposing onto the city a network of four buildings: a sports stadium, a church, a cultural center, and a Unité d’Habitation. The fourteen-story Unité d’Habitation consisted of 414 apartments with up to six rooms each, along with “dwelling extensions,” public spaces, a preschool, and a roof area with a combined playground and open-air theatre. The building was oriented along a north-south axis, with windows marking the beginning and ending points of the sun’s daily passage. Each apartment extended from the east to the west façade of the building, with a change of level in the central axis. In this way, each dwelling was provided with an open space extending over two floors with an office loft (or sometimes the parents’ bedroom) opening onto the living room. Le Corbusier used this and other open spaces, including children’s rooms that could be divided and varied by means of sliding doors, to create an architectural environment strongly oriented to communal structures.

Although the building was eventually completed in 1967, over the course of the nineteen-seventies, more and more tenants moved out. By 1982, all the residents had moved into the southern half of the structure. Access to the north part was blocked by a Plexiglas panel, permitting a view into the decaying north end of the building. Christian Philipp Müller became aware of the condition of the structure in 1988 during research for the exhibition “Porte bonheur” (1989). Following the exhibition, he and Yves Aupetitallot, then curator of the Maison de la Culture et de la Communication Saint-Étienne, decided to make the decaying Unité d’Habitation the focus of a site-specific art exhibition.

Five years later, “Project Unité” was realized on the seventh floor of the closed north half of the building. With Aupetitallot, the 28 empty apartments were handed over to an invited selection of around 40 artists, artists’ groups, and architects. Their works explored present-day socio-economic and cultural aspects that contributed to the failed utopia of modernist city planning in Firminy. The apartments themselves were renovated only in part, for the primary concern was to preserve the existing condition of the site to show its current state of decay. In accord with the architecture of the Unité, Aupetitallot also included transitional spaces and common rooms in the exhibition, using them as information centers, lounges, and meeting rooms for the presentation of similar projects, along with an information room on the Unité d’Habitation of which the residents had conceived. Prior to the exhibition, Müller had designed a newsletter which was published in three issues describing the plans for the project as well as the social conditions in the Unité.

In his own project (Apartment 389), however, Müller emphasized not only the progressive communalization Le Corbusier envisioned, but also a luxurious isolation. Upon entering the apartment, which constituted less the site than the object of the exhibition, visitors immediately found themselves in a muted environment. The walls were painted beige rather than bright white, while the glaring neon light at both ends of the spatial axis was softened by insulating curtains. The window fronts on both the east and the west sides were equipped with curtains that provided insulation against moisture, light, and noise, and created a cocoon-like environment. Along the entire length of the apartment, a series of gold-framed prints hanging at eye level showed the results of an acoustic study as well as tests of the insulation material and the apartments, with calculations for effective noise insulation in the dwellings. Each frame showed a document from this study and was accompanied by a label giving an English translation of the French text. Free copies of the acoustic study were available to residents and guests. In “Project Unité,” the diverse uses of the building, the utopian ideals on which it was based and its failures were developed in the apartments themselves and placed into relation to the current state of decay of Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation. Müller, on the other hand, transformed Apartment 389 into a protected individual space with a level of luxury too costly for the economically disadvantaged residents of the Unité.